How well meaning academic activism lost its way while battling destructive pseudoscience

As the US government, driven by Project 2025’s Christian Theocracy ideology, attempts to bully free thought off of our academic campuses, many people are unaware of a similar effort to stifle ideas coming from the rigid ideological left on our campuses.

The far right has a long history of misusing science to justify aggressive xenophobia such as racism and antisemitism. The pseudoscientific “eugenics” movement was the cornerstone of Naziism and was responsible for the sterilization of an estimated 64,000 people in the US in the early 20th century. (The Social Genome, p 32)

The assumption used by proponents to justify these horrible, inhumane movements is that a person’s ability is solely governed by their genetic makeup.

For nearly 100 years the dam that held back eugenicists’ efforts to institutionalize xenophobia was the academic left’s commitment to the idea we all start out as “blank slates” – our behavior is entirely learned after birth. The fact that it was as scientifically inaccurate as the eugenics view in no way lessens the importance of the role it played in paving the way toward equal rights for all – which we will see in future essays is scientifically justified. It has been a foundational plank of equal rights and opportunities for all people, particularly women and minorities in the developed countries.

But we shall see that science has shown that our behavior is much more complex that either a blank slate or absolutely deterministic genes – and the anti science blank slate academic is as misguided as the anti science religious zealot.

In the first half of the twentieth century, the Blank Slate concept was actively advocated by the young sciences of psychology, anthropology, and sociology.

The academic view of human nature was summed up by famous American psychologist John B Watson in his 1930 book “Behaviorism”:

“Give me a dozen healthy infants… and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select—doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief, and yes, even beggar-man and thief…”

This was echoed in 1955 by anthropologist Ashley Montagu in his book “The Nature of Human Aggression”:

“Man is man because he has no instincts, because everything he is and has become he has learned, acquired, from his culture … with the exception of the instinctoid reactions in infants to sudden withdrawals of support and to sudden loud noises, the human being is entirely instinctless.”

By the 1950’s, psychology was increasingly relying less on random observation and subsequent theories , and more on disciplined scientific studies.

By the 1970’s Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky had established that humans had predictable patterns or reasoning flaws – we are not naturally rational. Kahneman received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 for his work establishing humans don’t act rationally. (Note that the economic concept that humans act rationally still permeates economic policy world wide).

Then in the middle 70s, the most unlikely of people unwittingly created a firestorm of anti science campus activism that continues to this day.

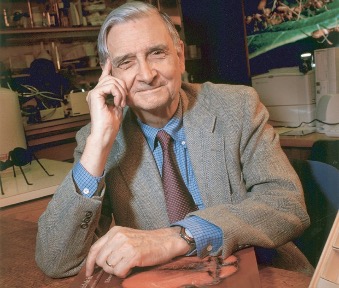

In 1975, Harvard professor Edward O Wilson published “Sociobiology”. The first 25 chapters deal with the biological basis for social behavior among animals from insects to non-human primates. The 26th chapter mused that human social behavior might have biological underpinnings. This set off the fire storm that continues today.

First, Marxists all over the world were outraged at the possibility there might be innate predispositions that ran counter to the selfless commitment to the state they view as humanity’s salvation.

Feminist activists quickly and vehemently followed, including physical attacks that were more symbolic than harmful– but indicated a visceral anger rather than rational disagreement.

Here is one of many commentaries by Edward O. Wilson, who was clearly unprepared for the level of vitriol opposed to scientific discussion:

Edward O. Wilson: Science and Ideology: “I had been blindsided by the attack. Having expected some frontal fire from social scientists on primarily evidential grounds, I had received instead a political enfilade from the flank. A few observers were surprised that I was surprised. John Maynard Smith, a senior British evolutionary biologist and former Marxist, said that he disliked the last chapter of Sociobiology himself and “it was also absolutely obvious to me —I cannot believe Wilson didn’t know— that this was going to provoke great hostility from American Marxists, and Marxists everywhere.” But it was true that I didn’t know. I was unprepared perhaps because, as Maynard Smith further observed, I am an American rather than a European. In 1975 I was a political naive: I knew almost nothing about Marxism as either a political belief or a mode of analysis; I had paid little attention to the dynamism of the activist Left, and I had never heard of Science for the People. I was not an intellectual in the European or New York/Cambridge sense. …

After the Sociobiology Study Group exposed me as a counterrevolutionary adventurist, and as they intensified their attacks in articles and teach-ins, other radical activists in the Boston area, including the violence-prone International Committee against Racism, conducted a campaign of leaflets and teach-ins of their own to oppose human sociobiology. As this activity spread through the winter and spring of 1975-76, I grew fearful that it might reach a level embarrassing to my family and the university. I briefly considered offers of professorships from three universities — in case, their representatives said, I wished to leave the physical center of the controversy. But the pressure was tolerable, since I was a senior professor with tenure, with a reputation based on other discoveries, and in any case could not bear to leave Harvard’s ant collection, the world’s largest and best.

For a few days a protester in Harvard Square used a bullhorn to call for my dismissal. Two students from the University of Michigan invaded my class on evolutionary biology one day to shout slogans and deliver anti- sociobiology monologues. I withdrew from department meetings for a year to avoid embarrassment arising from my notoriety, especially with key members of Science for the People present at these meetings.

In 1979 I was doused with water by a group of protestors at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, possibly the only incident in recent history that a scientist was physically attacked, however mildly, for the expression of an idea.

In 1982 I went to the Science Center at Harvard University under police escort to deliver a public lecture, because of the gathering of a crowd of protestors around the entrance, angered because of the title of my talk:

The coevolution of biology and culture.”

After Wilson died in late 2021, it was scant months before at least 2 articles accusing him of being a racist, one an op-ed in Scientific American. Both were personal attacks. Neither addressed his scientific work.

Over the ensuing 50 years the battle against sociobiology has continued with disturbing success on our campuses and in swaying the public’s view of ourselves.

Steven Pinker: Evolution and Behavior

While the geneticists and neuroscientists that are finding new structural underpinnings for our behavioral predispositions every day seem to be somewhat insulated from personal attack, evolutionary psychologists like Steven Pinker are not so lucky. Pinker is a Harvard professor who has written numerous popular books including “How the Mind Works”, “The Blank Slate”, and “The Better Angels of Our Nature”.

Among many other things in his books, he shares the science indicating that men and women evolved differently while in no way indicating or even implying that should define their roles in modern society. Yet there seems to be a cottage industry dedicated to attacking him personally. One graduate student at the American Museum of Natural History suggested that his acquaintance with Jeffery Epstein meant “Jeffrey Epstein loved evolutionary psychology And … evolutionary psychologists loved him right back.”

Like so many of the attacks on Pinker and other evolutionary psychologists, it has nothing to do with the science. It is written in anger and with the intent to inflame passion in others – not logic.

Unfortunately, Epstein was a very bright individual who managed to impress and become friends with quite a number of academics. But whatever his view of evolutionary psychology, it is an irrelevant factor in assessing the science illuminating it. And there is no hint of justifying uncivilized behavior in Pinker’s writing.

It is telling that character assassination continues to be the academic left’s primary tool for challenging science.

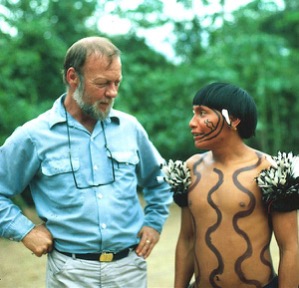

Napoleon Chagnon : objective anthropology

Since its birth in the 19th century anthropology has tended to be more focused on advocating for the groups it studies than in data driven, objective study. Notable and influential anthropologists like Margaret Mead and Ashely Montagu strongly supported the blank slate approach to explaining human behavior.

The result has been to actively squelch academic work that portrays primitive tribes as having the same behavioral predispositions as the rest of humanity.

Nowhere has this been more evident than in the assault against Napoleon Chagnon. See Alice Dreger’s Darkness’s Descent on the American Anthropological Association – she has done extensive research on Chagnon because as she says, “I had decided to carefully investigate Chagnon’s story because his was said by scientists I now trusted to illuminate like no other the dangerous intellectual rot occurring within certain branches of academe—the privileging of politics over evidence.” (emphasis mine) (Dreger, Alice. Galileo’s Middle Finger: Heretics, Activists, and One Scholar’s Search for Justice (p. 139). ).

Dreger goes on to say the reason that the American Anthropological Association allowed Chagnon’s career to be destroyed was because:

“Chagnon’s growing public fame had been steadily matched by growing infamy within his own field. That was in part because Chagnon had been an early and boisterous defender of sociobiology, the science of understanding the evolutionary bases for behaviors and cultures. (emphasis mine) Even so, by Chagnon’s time, all anthropologists believed in human evolution, and so his interest in studying humans as evolved animals might never have gotten him in so much trouble were it not for a couple of other things. First, Chagnon saw and represented in the Yanomamö a somewhat shocking image of evolved “human nature”—one featuring males fighting violently over fertile females, domestic brutality, ritualized drug use, and ecological indifference. Not your standard liberal image of the unjustly oppressed, naturally peaceful, environmentally gentle rain-forest Indian family. Not the kind of image that will win you friends among those cultural anthropologists who see themselves primarily as defenders of the oppressed subjects they study, especially if you’re suggesting, as Chagnon was, that the Yanomamö showed us our human nature.” (my emphasis).

The attacks on Chagnon, like the attacks on Wilson and Pinker were focused on the individual – not the science – with the intent to undermine the science.

Character assassination has become the anti-science weapon of the academic left. It is so much easier to wield than the complicated world of scientific facts.

Conclusion

This anti science anger from the left is based in the fear that scientific truths will be misconstrued to justify marginalizing women and minorities. It is clear that those who continue to attack scientists believe they are protecting the rights of women and minorities.

This blog will argue that only by understanding the roots of our behavior can we learn to curb our innate flaws- and that we must curb them in order to survive as a species.

Trying to change our behavior by denying the roots of it has reached the limits of its usefulness. Our ability to destroy the world by action in the case of nuclear war and climate change, or inaction in the case of pandemics or cosmic events, has made it imperative that we learn to cooperate now.

We cannot afford to allow rigid ideology driven anti science factions to derail our efforts to understand ourselves.

Postscript

The campus pressure from the left to muzzle dissent and root all academics in political activism is broader than just opposing behavioral science. Many people on the left are very concerned about the impact this is having our campuses. Below are links to some representative articles and letters:

A Letter on Justice and Open Debate, Harpers Magazine, 07-07-2020

“Can this man save Harvard”by Franklin Foer , Atlantic Magazine 07-18-2025

THE MULTIBILLION-DOLLAR FOUNDATION THAT CONTROLS THE HUMANITIES, Atlantic Magazine 02-12-26

Persecution of Scientists Whose Findings Are Perceived As Politically Incorrect, Sciencebasedmedicine.org, 02-16-2016